Memory models

Method of Loci

- For memorizing lists, sequential information

Spaced Repetition

“You can get a good deal from rehearsal,

If it just has the proper dispersal.

You would just be an ass,

To do it en masse,

Your remembering would turn out much worsal.”

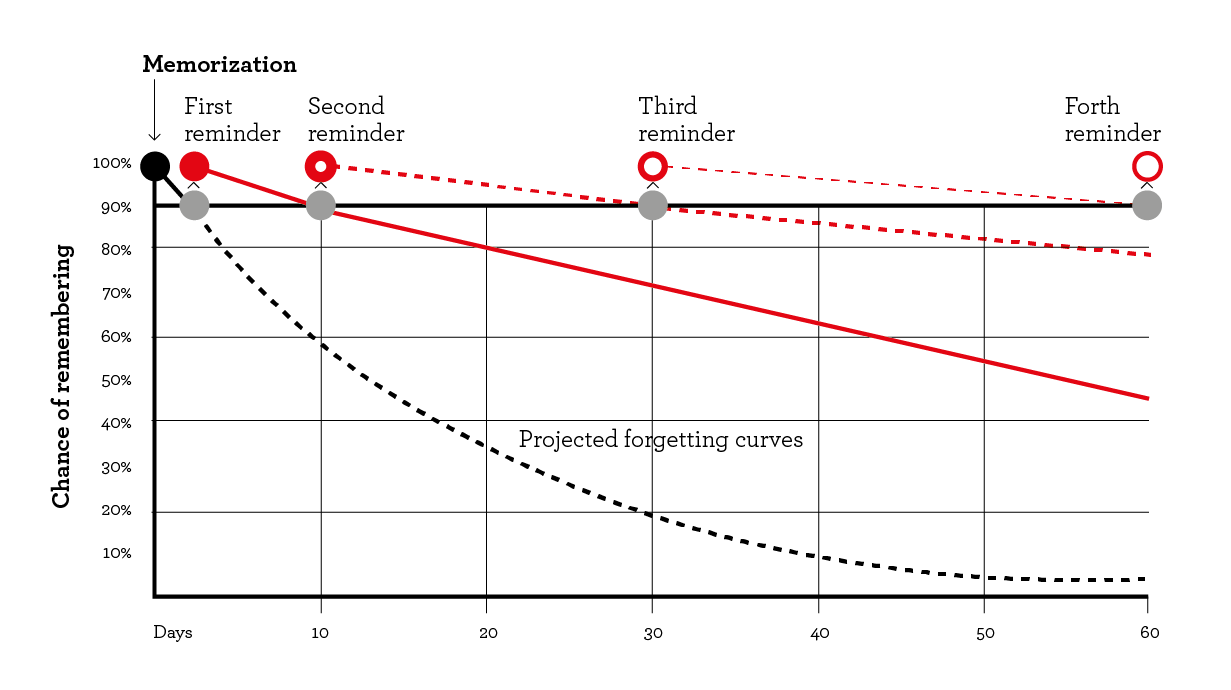

- Use the spacing effect to remind yourself of something just before you forget, extending the period of time before which you need another review. This prepares you best for long-term memorization, as the forgetting curve becomes less steep each time you review

- Forgetting curve as a radioactive half life

- A recency tradeoff to be made; one must determine how much a weight to place on knowing something in the future. Just like RL, one must discount future reward in preference for the present (as there is more uncertainty in the future, and to maximize total expected reward one must stake some claim now when near certainty is available). This is tradeoff to be made when “cramming” for an exam; is it worth passing the exam, but almost immediately forgetting everything? There needs to be a proper discount, not one too heavily rooted in the present.

Active recall

Active recall vs passive exposure, important to involve your memory during the learning process rather than mindlessly reviewing information

A nifty quote in advocation:

“If you read a piece of text through twenty times, you will not learn it by heart so easily as if you read it ten times while attempting to recite from time to time and consulting the text when your memory fails.” – The New Organon, Francis Bacon

Anki

A nice rule of thumb: if memorizing something will save 5 minutes in the future (or is worth 5 minutes of your time), it’s worth using SR to memorize. With Anki it takes 5 minutes to memorize something.

The process of working with Anki does more than just help you memorize things. The process of deciding what to remember, breaking concepts into integrative questions, etc; the involved nature of entering valuable, long-term information into the system is an effective learning process in and of itself.

Can be beneficial to add mutliple, highly connected variants of a particular question or topic. An example of this (from Augmenting Long-term Memory) might be asking the two questions: “What does Jones 2011 claim is the average age at which physics Nobelists made their prizewinning discovery, over 1980-2011?” And: “Which paper claimed that physics Nobelists made their prizewinning discovery at average age 48, over the period 1980-2011?” Here the two questions are highly related, but give two perspectives on the same fact.

Of course, it’s not just enough to put things into Anki. Just becuase you memorized a particular fact doesn’t mean you’ll recognize the proper context to use it effectively. You must also “carry out the process, in context”. This is the difference between declarative and procedural memory. A nice related Feynman quote:

One kid says to me, “See that bird? What kind of bird is that?”

I said, “I haven’t the slightest idea what kind of a bird it is.”

He says, “It’a brown-throated thrush. Your father doesn’t teach you anything!”

But it was the opposite. He [Feynman’s father] had already taught me: “See that bird?” he says. “It’s a Spencer’s warbler.” (I knew he didn’t know the real name.) “Well, in Italian, it’s a Chutto Lapittida. In Portuguese, it’s a Bom da Peida… You can know the name of that bird in all the languages of the world, but when you’re finished, you’ll know absolutely nothing whatever about the bird! You’ll only know about humans in different places, and what they call the bird. So let’s look at the bird and see what it’s doing — that’s what counts.” (I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.)

What to add

- Gwern references Funes the Memorious when considering what to add to an SRS. When adding everything, you almost surely will add things that you don’t really care about. You then decentivize yourself to review the cards, and find yourself on a slippery slope (Schelling fences on slippery slopes) until you completely stop using the system.

- Keep questions atomic; it’s best to be worthing with a very fundamental phrasal of the concept so it’s easy to know where to direct your focus and identify what goes wrong when you fail. If you find a question to difficult to remember properly, consider breaking it into multiple questions, each of which addess some finer atomic structure in the original question. As noted by Michael Nielson, this can be an effective technique. Note that it might also make sense to keep the original question around, as it embodies the original concept/idea you wanted to know. This is the process of building rich, hierarchical, integrative questions and can be an effective way to understand deeper, more involved topics.